This is the first year Chloe’s Fight Rare Disease Foundation has participated in Give to the Max. Participation is super easy. Either mark your calendar for a day-of donation, or donate today in advance. It’s generous donors like you who will make the world a better place for children with a rare disease – thank you!

Click on the logo below to donate to Chloe’s Fight as part of our Give to Max campaign.

(First published as an

(First published as an  As America’s lawmakers debate various ways to fix our broken health care system, we in the rare disease community are alarmed by proposed cuts to Medicaid funding. The term “rare disease” is a bit paradoxical. When viewed individually, a particular disease may affect a minuscule portion of the population. But when considered as a whole,

As America’s lawmakers debate various ways to fix our broken health care system, we in the rare disease community are alarmed by proposed cuts to Medicaid funding. The term “rare disease” is a bit paradoxical. When viewed individually, a particular disease may affect a minuscule portion of the population. But when considered as a whole,

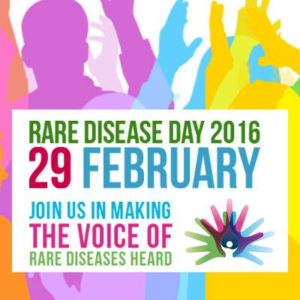

February 28th is internationally recognized as Rare Disease Day. My daughter, Chloe, was diagnosed with a rare and terminal disease at the age of two in a miraculously short time due to the brilliance of her neurologist. The neurologist was Canadian. Chloe’s only hope of survival was a bone marrow transplant, a risky and arduous procedure. We put our youngest child’s life in the hands of a capable and caring surgeon at the Mayo Clinic. She was Pakistani. Throughout the transplant there were long days of agony and fear as we awaited the outcome. Since her immune system was completely gone, neither she nor I could leave our tiny ICU room. The resident on the medical team brought me a Starbucks coffee each morning. He was Egyptian. When it became clear that Chloe’s chances for survival were non-existent, we met with the team to decide whether to try a risky and painful second transplant or let her go. I shared with the doctors that I believed deeply in medicine but also that, at the end of the day, my Christian faith informed me that it is God who decides how many days we have on this earth. I sensed that my decision resonated deeply with my Pakistani doctor’s faith as well. She was a Muslim.

February 28th is internationally recognized as Rare Disease Day. My daughter, Chloe, was diagnosed with a rare and terminal disease at the age of two in a miraculously short time due to the brilliance of her neurologist. The neurologist was Canadian. Chloe’s only hope of survival was a bone marrow transplant, a risky and arduous procedure. We put our youngest child’s life in the hands of a capable and caring surgeon at the Mayo Clinic. She was Pakistani. Throughout the transplant there were long days of agony and fear as we awaited the outcome. Since her immune system was completely gone, neither she nor I could leave our tiny ICU room. The resident on the medical team brought me a Starbucks coffee each morning. He was Egyptian. When it became clear that Chloe’s chances for survival were non-existent, we met with the team to decide whether to try a risky and painful second transplant or let her go. I shared with the doctors that I believed deeply in medicine but also that, at the end of the day, my Christian faith informed me that it is God who decides how many days we have on this earth. I sensed that my decision resonated deeply with my Pakistani doctor’s faith as well. She was a Muslim.

Driving home from work last week it was surreal to listen to local news coverage of the live press conference in Chanhassen, MN, knowing that the whole world was tuning in to my home town. Local law enforcement was addressing the public outside of Paisley Park, home of the rock legend Prince who, of course, had just died. The grief for us Minnesotans is unique and multilayered because Prince, while being an intensely private man, was also deeply embedded in his Minneapolis community and its suburbs where he was born and raised. After the renovation of the Minneapolis fixture the Uptown Theater, a local movie critic mentioned in passing that Prince occasionally slipped in to watch a film. (It became my habit after that to scan the audience to see if he and I had the same cinematic taste.) He had his own private table at the Dakota Jazz Club downtown. Some of my friends live a few doors down from one of his rental properties. I had even heard that he would once in a while do some door to door evangelizing for his small church located in St. Louis Park just minutes from my own home.

Driving home from work last week it was surreal to listen to local news coverage of the live press conference in Chanhassen, MN, knowing that the whole world was tuning in to my home town. Local law enforcement was addressing the public outside of Paisley Park, home of the rock legend Prince who, of course, had just died. The grief for us Minnesotans is unique and multilayered because Prince, while being an intensely private man, was also deeply embedded in his Minneapolis community and its suburbs where he was born and raised. After the renovation of the Minneapolis fixture the Uptown Theater, a local movie critic mentioned in passing that Prince occasionally slipped in to watch a film. (It became my habit after that to scan the audience to see if he and I had the same cinematic taste.) He had his own private table at the Dakota Jazz Club downtown. Some of my friends live a few doors down from one of his rental properties. I had even heard that he would once in a while do some door to door evangelizing for his small church located in St. Louis Park just minutes from my own home. Before my daughter passed away from a rare disease I had never heard of “Rare Disease Day” and knew next to nothing about the impact rare disorders have on society. Over the past few years I have learned that rare diseases play a larger role in public health than most people realize and deserve consideration from the medical community, policy makers, and the general public.

Before my daughter passed away from a rare disease I had never heard of “Rare Disease Day” and knew next to nothing about the impact rare disorders have on society. Over the past few years I have learned that rare diseases play a larger role in public health than most people realize and deserve consideration from the medical community, policy makers, and the general public.